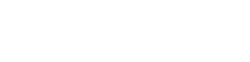

Who is Selina Hastings?

I recently had to write an essay on a significant contributor to the 18th century revival in England and beyond. With my ties to Huntingdon Hall in Worcester, I chose Lady Selena Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. Below is an abridged version of that essay which I hope you will find useful. Much of my research came from Faith Cook’s fantastic biography Selina, Countess of Huntingdon. You can find my review of the biography here.

What contribution did Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, make to the Evangelical Awakening in England? What can we learn from her about how to serve God in our day however different it may be?

Introduction and conversion

Selina Hastings (1707-1791) was born into wealth and aristocracy. Aged 21, she married Theophilus Hastings, the 9th Earl of Huntingdon, thus becoming the Countess of Huntingdon. Selina’s conversion was a long and unpleasant journey. At the age of 9, Selina witnessed the funeral pyre of a girl her own age. From then until her early 30s, Selina grappled with disillusionment amidst the prevalence of death in her early life. By God’s grace, she was dramatically converted to the Christian faith in 1739. Facing the real possibility of her own death due to serious illness, she pondered sending for someone to spiritually counsel her when ‘she felt an earnest desire... to cast herself wholly upon Christ for life and salvation.’ Selina’s new zealous faith paired with her wealth, influence and connections proved to be a potent force for the growth of the revival in the 18th century.

The beginning of her work

‘With her conversion came a deepening concern for the welfare of the men and women on her estates and a zeal for the salvation of her servants, her acquaintances, her family and the nobility amongst whom she mingled.’ So, Selina held household meetings of all domestic staff where she would follow a reading from a religious book with an exhortation to seek salvation. This enterprise would grow to include her social circle. ‘As a peeress, she had the legal right to appoint two private chaplains whose responsibility it was to minister to the spiritual needs of her household wherever she might be living. If she appointed George Whitefield to this position, she could then invite members of the nobility, politicians and even royalty to her home to listen to her chaplain preach.’ Many celebrities of the day would attend and a significant few were converted. Such was the magnitude of Selina’s initiative that a biographer of George Whitefield writes, ‘These gatherings... were profoundly interesting spectacles; and never till the Day of Judgment will it be ascertained to what extent the preaching of the youthful Whitfield affected the policy of some of England’s greatest statesmen and moulded the character of some of England’s highest aristocratic families.’

Selina’s influence

Though primarily focussed on the ministries of her own chaplains, Selina also had a vested interest in the ministries of all evangelical preachers. Her position in the aristocracy was key to her effectiveness in this area. For example, when Baronet Watkin William Wynn imposed fines on listeners to the preaching of Howell Harris, Selina complained to the government about Watkin’s behaviour which resulted in the fines returning to their owners. This is just one example of how Cook describes ‘The Countess used her unquestionable influence in the highest circles of the land and even in the royal court to throw the cloak of her protection over the prominent preachers of the day and over the fledging Methodist movement itself.’

Though a Methodist, Selina always remained loyal to the Church of England and wished to see it reformed from the inside. Here, again, ‘by means of her influence in the highest places of the land, [Selina] determined to bring pressure on the bishops to ordain men who held to the truths of the gospel.’ Upon meeting such men and confirming their dedication, Selina would press bishops to accept these men. This practise was ‘unquestionably the principal means of effecting the marvellous change that has taken place since then in the Established Church.’

Chapel building

As obtaining ordination for evangelical preachers became increasingly difficult, Selina took the next step in the growth of the gospel. ‘If she, with her privileges as a peeress, were able to assist in financing new buildings or in purchasing the lease of existing ones, this would provide places of worship where evangelical men could preach without the strictures often imposed upon them by the hierarchy of the Church.’ This would prove to be an extremely effective enterprise. Even in her last decade, a letter dated 1785 reveals 10 chapels built in 5 months. By 1788, the Countess compiled a list of no fewer than 116 ‘preaching places’ for which she was responsible. Nick Needham writes that ‘over 200 chapels were constructed, either fully or partly funded by Hastings.’ This could debatably be considered her greatest contribution to the Evangelical Awakening due to sheer number of doors of opportunity to preach the gospel, and congregations would regularly comprise of hundreds of people.

Trevecca training college

The culmination of Selina’s efforts to spread the gospel far and wide was her partnership with Howell Harris to create the Trevecca training college. By acquiring ordination for some preachers, other preachers aging, and others still caught up in business, ‘sometimes the Countess was quite unable to find preachers able and willing to supply the preaching stations she had set up.’ Thus, she began to bring to fruition a plan she had been steadily forming in her mind: ‘a place where men of evangelical conviction could be trained and then sent out to supply the vacant pulpits.’ The college had its up and downs through Selina’s life, but its productive impact cannot be dismissed. Upon meeting Selina, King George III was mightily impressed with her and her college. ‘Whilst the king might wish he had a Lady Huntingdon in every diocese of his kingdom, he could never have conceived of the way in which her influence was about to spread throughout the land during the next 10 years of his reign as the students of Trevecca College travelled tirelessly preaching wherever they went.’ ‘Trevecca’s influence was to be even more widespread as it set the pattern for the training of preachers which would be followed by other institutions.’ It is safe to conclude, as Thomas Wills does, that ‘thousands, I may say tens of thousands, in various parts of the kingdom heard the gospel through her instrumentality that in all probability would never have heard it at all.’

Her Christian service

Though written 250 years ago, Cardinal John Henry Newman’s comments on the Countess of Huntingdon still ring relevant for Christian service today. They present a model of true Godliness in her focus on eternity, her generosity, and her abundantly sacrificial heart:

‘What pleases us is the sight of a person simply and unconditionally giving up this world for the next. Lady Huntingdon sets Christians of all time an example. She devoted herself, her name, her means, her time, her thoughts, to the cause of Christ. She did not spend her money on herself, she did not allow the homage paid to her rank to remain with herself: she passed these on and offered them up to him from whom her gifts came. She acted as one ought to act who considers this life a pilgrimage, not a home. She was a representative… of the rich becoming poor for Christ, of delicate women putting off their soft attire and wrapping themselves in sackcloth for the kingdom of heaven’s sake.’

Whilst Newman provides a wonderful overview of her Godly character and service, there are other evident particulars in Selina’s character and service that Christians today could learn from.

Though she became slightly obstinate in later life, Selina remained extraordinarily forbearing for much of her life. Rowland Hill made public jokes at her expense in 1782 yet when plans for his London church were being laid that year, ‘the Countess wrote to a friend commending Hill’s abilities and evangelistic zeal. More than this, she sent a contribution for the proposed chapel.’ She also made peace with the Wesley brothers over the 1770 Minutes controversy even though John Wesley had insulted her greatly through a ‘bitter’ letter in the same year.

Selina was also immensely compassionate, shown in her pity for sinner’s souls, her great concern for those who were far less fortunate than she was, and her practical care of those she loved who were ill. When visiting Bristol in 1749, Selina visited a debt prison and she ’is known to have relieved at least 34 debtors who owed £10 or less during this period. She would make good the debt herself and so restore the prisoner to his family.’

Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntingdon, was a great Godly lady and an immense contributor to the revival in 18th century UK and Ireland. She goes largely unknown, due to her own desire to not be publicised, but her influence has shaped the ecclesiastical and evangelical landscape of those nations. Her heart for the Lord, her generous purse, and her sacrificial nature are, by God’s grace, spiritual fruits Christians should strive for today.